A Google Earth for the universe: VR space exploration software builds amazing 3D renditions of everything, from the International Space Station to Saturn and beyond

- A Swiss university is releasing free software for virtual views – close up and far away – of objects in space

- From the International Space Station to the planets, solar system and universe, the 3D views are incredible

Researchers at one of Switzerland’s top universities are releasing open-source beta software that allows for virtual visits through the cosmos including a trip to the International Space Station, the moon, Saturn over galaxies and well beyond.

The programme – Virtual Reality Universe Project, or Virup – pulls together what the researchers call the largest data set of the universe to create three-dimensional, panoramic visualisations.

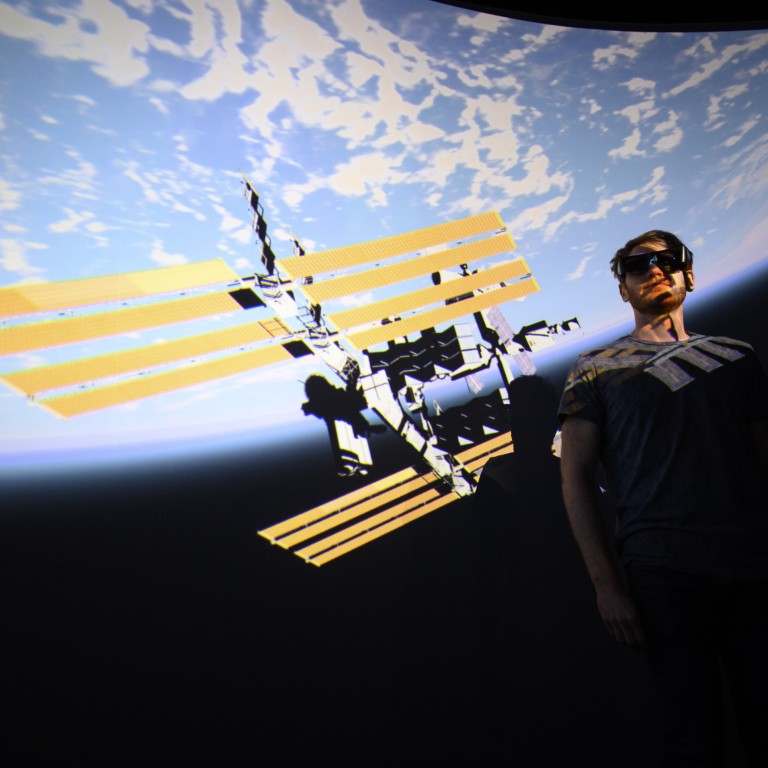

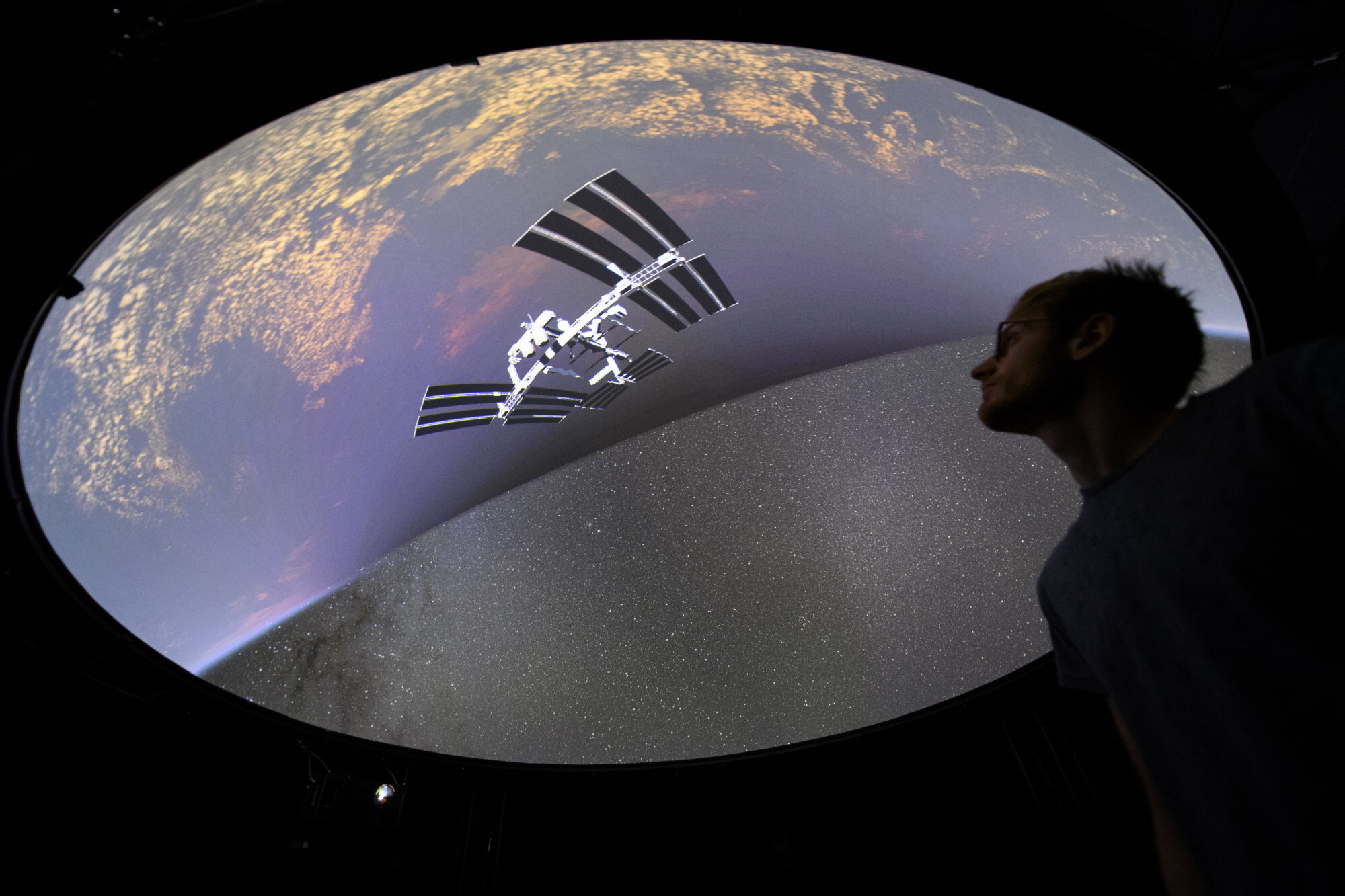

Software engineers, astrophysicists and experimental museology experts at the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, or EPFL, have come together to concoct the virtual map that can be viewed through individual VR gear, immersion systems like panoramic cinema with 3D glasses, planetarium-like dome screens, or a PC for two-dimensional viewing.

“The novelty of this project was putting all the data available into one framework, when you can see the universe at different scales – near us, around the Earth, around the solar system, at the Milky Way level, to see through the universe and time up to the beginning – what we call the Big Bang,” says Jean-Paul Kneib, director of EPFL’s astrophysics lab.

Think a sort of Google Earth – but for the universe. Computer algorithms churn through terabytes of data and produce images that can appear as close as one metre (about 3 feet), or an almost infinite distance – as if you sit back and look at the entire observable universe.

Virup is accessible to everyone at no cost – although it does require at least a computer and is best visualised with VR equipment or 3D capabilities. It aims to draw in scientists looking to visualise the data they collect, and a broad public seeking to explore the heavens virtually.

‘Factory of discoveries’: China aims high to explain the universe

Still a work in progress, for now, the beta version can’t be run on a Mac computer. The broader-public version of the content is a reduced-size version that can be quantified in gigabytes, a sort of best-of highlights. Astronomy buffs with more PC memory might choose to download more.

The project assembles information from eight databases that count at least 4,500 known exoplanets, tens of millions of galaxies, hundreds of millions of space objects in all, and more than 1.5 billion light sources from the Milky Way alone. But when it comes to potential data, the sky is literally the limit. Future databases could include asteroids in our solar system or objects like nebulae and pulsars farther into the galaxy.

To be sure, VR games and representations already exist: cosmos-gazing apps on tablets allow for mapping of the night sky, with zoom-in close-ups of heavenly bodies; software like SpaceEngine from Russia offers universe visuals; Nasa has done some smaller VR scopes of space.

But the EPFL team says Virup goes much farther and wider. Data pulled from sources like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey in the US, and the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission to map the Milky Way and its Planck mission to observe the first light of the universe, all brought together for the most extensive data sets around.

And there’s more to come: when the 14-country telescope project known as the Square Kilometre Array starts pulling down information, the data could be counted in petabytes – that’s 1,000 terabytes or 1 million gigabytes.

Strap on the VR goggles, and it’s a trippy feeling seeing the moon – the size of a giant beach ball and floating close enough to hold – as the horizon rotates from the sunny side to the dark side of the lunar surface.

China gets ready to send second crew to space station for longer mission

Then swing by Saturn, then up above the Milky Way, swirling and flashing and heaving – with exoplanets highlighted in red. And much farther out still, imagine floating through small dots of light that represent galaxies.

“That is a very efficient way of visiting all the different scales that compose our universe,” says Yves Revaz, an EPFL astrophysicist.

“A very important part of this project is that it’s a first step toward treating much larger data sets which are coming.”

Entire galaxies seem to be strung together by strands or filaments of light, almost like a representation of neural connections. For one of the biggest pictures of all, there’s a colourful visualisation of the Cosmic Microwave Background – the radiation left behind from the Big Bang.

“We actually started this project because I was working on a three-dimensional mapping project of the universe and was always a little frustrated with the 2D visualisation on my screen, which wasn’t very meaningful,” says Kneib, in a nondescript lab building that houses a panoramic screen, a half-dome cinema with beanbag seating, and a hard-floor space for virtual-reality excursions.

“It’s true that by showing the universe in 3D, by showing these filaments, by showing these clusters of galaxies which are large concentrations of matter, you really realise what the universe is,” he added.